The Getty Center at 20

John Hill

13. December 2017

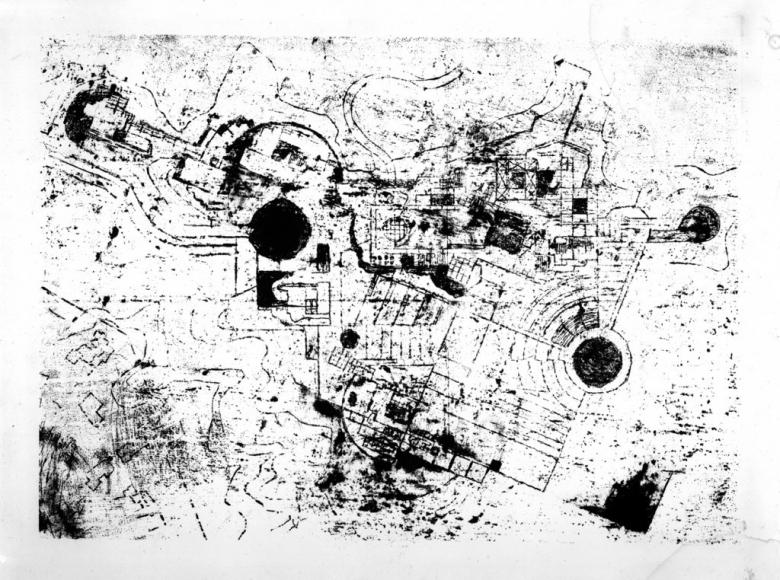

Early plan of the Getty Center (Drawing © Richard Meier & Partners Architects)

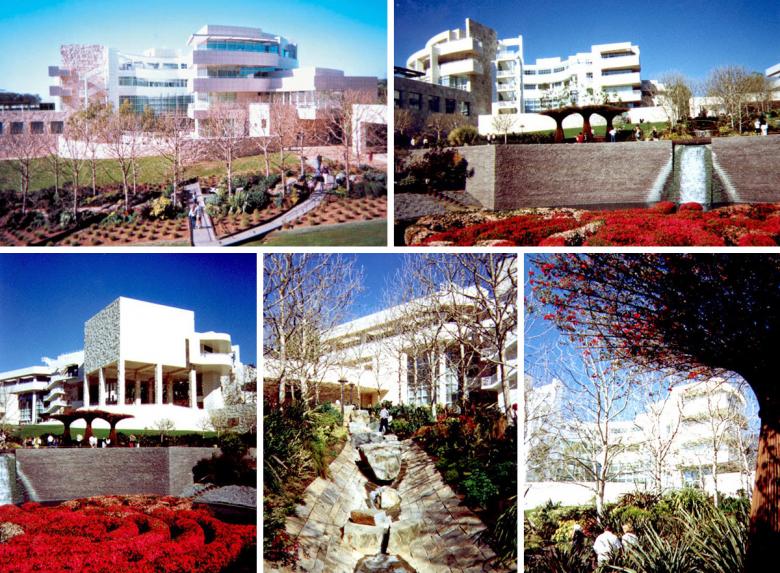

Twenty years ago, Richard Meier's Getty Center opened to the public on a hilltop overlooking Los Angeles. The institution is celebrating its anniversary with an exhibition of photographs taken just before the project's completion.

It was an odd thing in 1997: people were talking about architecture. It wasn't just architects talking though; everybody was talking about it. And they were talking about two projects: Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao, which was inaugurated on the 18th of October, and Richard Meier's Getty Center, which opened to the public on the 12th of December.

Many conversations debated the merits between the two projects, turning taste and preference into an either/or choice. I, for instance, preferred Gehry's flowing sheets of titanium, while my mother, not an architect, sided with Meier's geometric balancing act of travertine and his usual white aluminum. Then New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp boldly called Gehry's building "the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe," while he likened the Getty to a "mountain of marble" and "Los Angeles's stupendous new castle of classical beauty."

Yet the most distinctive difference between the two projects is not necessarily their formal attire; it is how they relate to their host cities. The Guggenheim embeds itself on a riverfront site in the post-industrial Basque city, but the Getty Center props itself atop an Acropolis-like hill so secluded it requires a tram ride from the parking lot or, as I did when I visited in 2003, from the bus stop.

Entrance Hall, J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997 (Photo © Robert Polidori)

Differences aside, both institutions are using the 20-year milestone to celebrate themselves through their architecture. Among other events, the Guggenheim put on a light show in October, turning the metal skin into a canvas for light. The Getty, on the other hand, has put on an exhibition, Robert Polidori: 20 Photographs of the Getty Museum, 1997, "the first public exhibition of photographs showing the first installation of the Getty Center in the month leading up to its opening in December 1997."

Beyond the Getty Center's constituent parts – Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Getty Museum, and Getty Research Institute – 2017 is also the 20th anniversary of its Central Garden, created by artist Robert Irwin. This wasn't always the case: early drawings and models reveal Meier's preference for a terrace bowl gently descending the landscape and exhibiting a geometric rigor that mirrors the buildings and landscapes of the rest of the Center.

Model of Getty Center at Richard Meier Model Museum showing the architect's version of the Central Garden. (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Irwin was brought on about halfway through the long process, a couple years after Meier's design was approved. Where Meier had simplicity and order, Irwin infused the garden with color and whimsy. "Their forced collaboration was strained," as I described in my book 100 Years, 100 Landscape Designs, but the garden and buildings "are anithetical but inseparable pieces of the place. It's difficult to imagine one without the other."

Not surprisingly, Meier does not share that attitude. The architect answered Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne's question, "Do you talk with [Irwin] at all?" with a simple "No." Pressed if he spoke with Irwin when the artist contributed another piece of public art, to Meier's federal courthouse in San Diego, Meier again replied, "No." Meier should be happy that the Getty Center's 20th anniversary celebrations focus on his architecture and the galleries they contain.