Interview with Liu Yichun of Atelier Deshaus

The Contemporaneity of Chinese Architecture

Eduard Kögel

24. March 2023

80,000-ton Silo Art Centre at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Tian Fangfang)

The exhibition COMMON LANDSCAPE. Re-Cultivating Industrial Sites by Shanghai’s Atelier Deshaus will open at Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin on March 31, 2023. The exhibition’s curator, Eduard Kögel, spoke with founding partner Liu Yichun about the firm’s architecture in advance of the opening.

Eduard Kögel: In 2001, when you founded Atelier Deshaus with your colleagues Chen Yifeng and Zhuang Shen (who left the firm in 2009), I curated, together with Ulf Meyer, the first exhibition on independent young Chinese architects outside of China. The exhibition “TUMU – Young Architecture from China” at Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin became an important reference for the perspective of foreigners on the architectural development in China at the time. You were in Berlin for the opening. What was your impression?

Liu Yichun: In 2001, when Atelier Deshaus was founded, I traveled around Europe with Zhuang Shen and Chen Yifeng. We did not make it to the opening ceremony, but visited the exhibition the following day. I wrote an essay, “Visiting Tu Mu: Exhibition of Young Chinese Architects in Berlin,” which was later published in DI magazine in Shanghai. This exhibition opened the window for China and the world in the field of architecture, and provided a unique view of Chinese architects abroad. “Experimental architecture” has become synonymous with pioneering Chinese architecture, while the independent architecture studio has also gradually become a goal for young architects. In my essay, I expressed my opinions on the use of the term “TUMU” [literally “earth and wood,” referring to tradition rather than contemporary practice] to identify the characteristics of Chinese architecture from a Western perspective. I felt that the works on display did not quit fit the theme of “TUMU.” In retrospect, maybe Wang Shu is perhaps the only one among them who still stubbornly adheres to these themes.

A lot has changed in the last 20 years and Atelier Deshaus has become an important driving force in the architecture scene in Shanghai and in China. What are the core topics your office deals with today?

Over the past 20 years, Atelier Deshaus has been closely associated with Shanghai’s development. However, our activity has shifted from suburban new town construction to urban regeneration projects in the central part of the city. The renovation projects of industrial areas along the Huangpu River have put the office in a good position, as the completion of the Deshaus-designed Long Museum on the West Bund received much attention both at home and abroad. Since then, the preservation and renovation of industrial architecture became one focus of our work. In the process, two themes have developed: One is the role of structure to space and its atmosphere, which emerged in the renovation of industrial buildings, and a quality that was lacking in contemporary Chinese architecture. The second aspect is how to deal with public space and landscape along the Huangpu River.

In considering how to work with existing industrial ruins, we have begun to shift from an initial interest in the abstract spatial experience of traditional Chinese gardens to the use of strategic methods such as “Yin Jie Ti Yi” in garden-making and how to maintain a sense of intimacy in a public space. “Yin Jie Ti Yi,” these four characters come from a garden manual entitled The Craft of Gardens (Yuan Ye) written by Ji Cheng in the late Ming dynasty. “Yin” means seizing productive contextual forces; “jie” refers to taking advantage of the surroundings; “ti” means formal states of rational existence; and “yi” refers to being appropriately situated. These references also influence our design of new buildings: to connect the quality of the interior space with the expression of structure, for example, or to define and establish the external image of the architecture by connecting structure and space with a particular site, etc. Looking at the issue in a broader context, we are generally still very much focused on the contemporaneity of Chinese architecture.

Long Museum West Bund at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Su Shengliang)

Long Museum West Bund at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Su Shengliang)

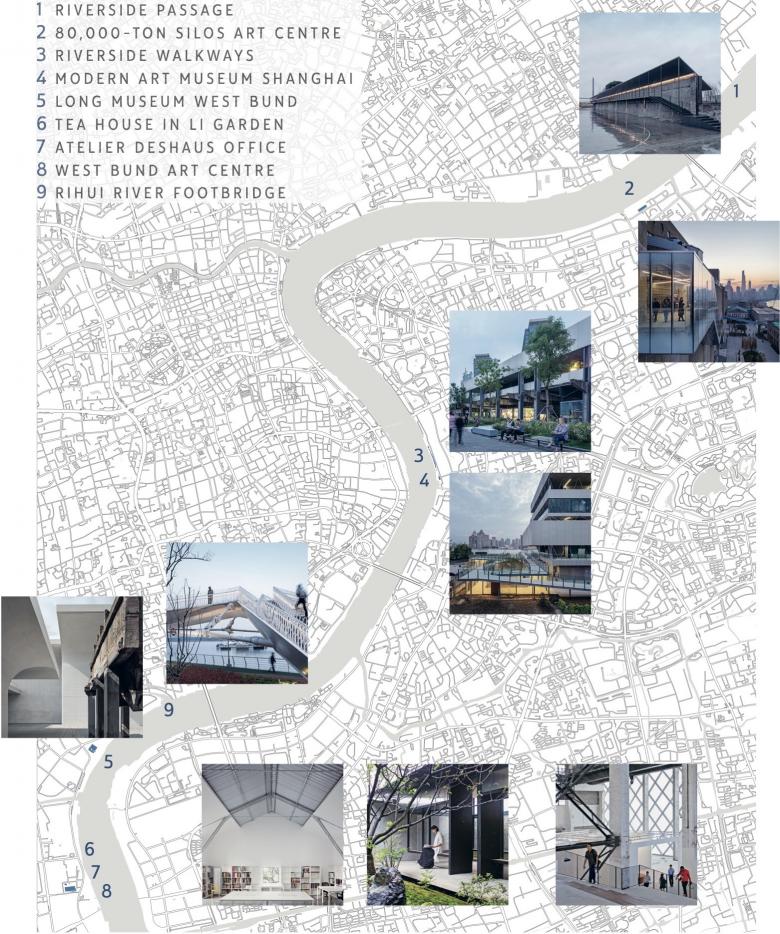

Atelier Deshaus's buildings along Huangpu River in Shanghai (Image © Atelier Deshaus)

The occasion for this interview is your exhibition at Aedes Architecture Forum in Berlin in April/May 2023, which focuses on the conversion of former industrial sites along the Huangpu River in Shanghai. How did Atelier Deshaus come to realize so many of these projects?

The influence of the Long Museum on the West Bund, completed in 2014, opened the door for other projects along the Huangpu River. Indeed, the Long Museum boosted public expectation and confidence in the renovation of Shanghai’s industrial riverfront, and brought us similar projects, from the West Bund to the Huangpu East Bank and later to the Yangpu Riverfront. This also goes hand in hand with Shanghai’s drive to open the riverfront to the public.

We did not consciously choose the industrial renovation projects, but the projects chose us. However, after completing several projects, such as the Long Museum in 2014, the Modern Art Museum in 2016, and the 80,000-ton Silos Art Centre in 2017, I realized that there are certain design concepts and directions worth exploring and developing further. In line with the references I talked about in the previous question, these include: how to fully preserve the existing while transforming it into contemporary urban space and how to bring our attitude towards the contemporary urban environment throughout the process.

The conversion projects are often complex and have many problems to solve. How does Atelier Deshaus work on the projects? Are there fixed project teams, and how does the collaboration with other disciplines, such as construction, proceed?

Deshaus does not have a permanent team of architects dedicated to renovation projects. All projects basically follow the same working pattern, except that the renovation projects start with a detailed mapping, inspection and evaluation of the existing buildings, usually carried out in collaboration with specialized companies. Among the collaborators with Deshaus, the structural design team AND Office is relatively fixed in the early stage of the project. They can engage in discussions as early as the schematic design phase. During these discussions, combined with consideration of other factors of the project, such as history, topography, and program, the framework of the architecture is gradually established, from which the tone of a space and its atmosphere are determined. This tone is maintained and reinforced in further development, and other disciplines must strive to fit in.

Modern Art Museum Shanghai at Huangpu River (Photo © Tian Fangfang)

Riverside Walkways on Laobaidu Wharf at Huangpu River (Photo © Tian Fangfang)

80,000-ton Silo Art Centre at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Tian Fangfang)

You cofounded the engineering company AND Office together with others. Why?

The establishment of AND Office mainly results from the dissatisfaction with the current situation of cooperation between architects and civil engineers in the Chinese building industry. There are hardly any independent structural engineering offices in China. The work flow in the big design institutes mainly consist of civil engineers fitting structural design to existing architectural schemes. On the one hand, this workflow restricts the role that structure can play in architecture and eliminates the possibility of imbuing the architecture with certain essential qualities. On the other hand, the work of structural engineers is rather mechanized, as their autonomy is only given in certain long-span structures and in the design of bridges. AND Office was founded to change the status quo of collaboration between architecture and structural engineering in Chinese building industry, especially to influence the role of structural engineers in the early stages of architectural design.

Is the company completely independent of Atelier Deshaus and how do you work with them?

As a company, AND Office is completely independent of Atelier Deshaus but works in the same building. The lead structural engineer is Zhang Zhun. The architects of Deshaus can immediately seek help and start discussions with AND Office for any construction-related issues, while the engineers also get to better know the architects’ way of thinking. Meanwhile, many other independent architects in China have started to work closely with AND Office.

Many of your projects have sophisticated construction systems that make the conversion of industrial ruins architecturally possible in this form in the first place. How do the approval authorities and clients react?

As for Deshaus’s renovation projects along the Huangpu River, both authorities and clients can experience and understand the end result in their own way. First and foremost, the authorities are in favor of preserving existing structures to reduce demolition. From an environmental perspective, this is a low-carbon solution that additionally helps preserve the city’s history. We try to present the new and old constructions with a clear visual logic so that the public understands how the effects of decay on architectural quality can be quite positive. Many of those who have worked at these sites are pleased to see their familiar workplaces transformed into new public spaces, and they express an intimate feeling for these places.

Riverside Passage at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Chen Hao)

Riverside Passage at Huangpu River in Shanghai (Photo © Tian Fangfang)

A beautiful example of a poetic interpretation of an industrial ruin is the Riverside Passage on Huangpu River. Here, you cleverly manipulated the existing structure with historical models from classical gardens in such a way that the spontaneously grown vegetation becomes the secret star of the project. Does the audience understand the allusions, and how do they find it?

The space of the Chinese garden has become a bodily memory for many of us. Judging by the activities that have taken place here since the completion of the project, I think that users intuitively understand the spatial intentions. People run through the open space of the dock and make themselves comfortable behind the wall in the more intimate part. Some elderly people do gymnastics exercises here or just chill for a while. The space feels expansive, but not oppressive. It gives the feeling that people are free to move around while enjoying possible solitude.

You are also very innovative when it comes to materials and new solutions. For example, the roof of the pavilion at the Upper Cloister is not only experimentally shaped, but also made of particularly light material. How do you find the optimal solution here and who carries it out? And how do you control the process?

It is true that I tend to explore the use of new structures and materials to bring contemporary technic or innovation to the project. The roof of the Zen Hall at the Upper Cloister corresponds to traditional wooden architecture. Since the pavilion roof is supported by extremely thin steel columns, we looked for lightness and slenderness in the form, which is inspired by the curved roofs of traditional wooden architecture. At some angles it may be more similar to the traditional roof, and in other directions it may evoke other associations. I like such ambiguity. The curved roof shell was ultimately built using a smart robotic arm and CNC carving combined with carbon fiber structural technologies. Since the project is in the mountains, the only way to ensure quality construction was with prefabrication. I brought in a digital fabrication team and designed the new building system with AND Office. I was fully involved throughout the construction process, as many details had to be resolved on site. On the construction site, there were still many errors for which the architects had to find a solution, including the surface paint, for which a satisfactory result was found after numerous experiments.

As far as the ideas for the space are concerned, I have the impression that you are orienting yourselves toward idealized models from historical China. The embedding in the topography, the guidance of people, the use of elements from garden architecture, such as openwork walls, can be found in historical garden settings. How important are historical references and how to you process them for your own purposes?

History is probably an identity code for me, but it’s also not a limitation. Whether it’s a recent history, such as with industrial remains, or a more distant history, as with traditional gardens, I’m fascinated by the way they can be brought into the contemporary construction of space. In this context, the word “coincidence” becomes essential for me. I always explore the meaning of these historical elements in today’s time and space, so that both tradition and today’s reality can be a starting point. My expectation of the result remain coincidence. Subjectively, I do not favor either side, but strive to find a connection between them.

Upper Cloister in Jinshan Mountain north of Beijing (Photo © Su Shengliang)

Upper Cloister in Jinshan Mountain north of Beijing (Photo © Su Shengliang)

The projects you were able to realize in Shanghai are very impressive. Are there other places in China that are now interested in your ideas for conversion, and have you already received offers in this vein outside Shanghai?

Of course. We are offered similar conversion projects from many other cities. But these types of projects require a thorough understanding of the site. Even if the design is carefully finalized, it may still need to be adjusted during the construction phase, as there are many specific issues to be resolved on site regarding dimensions and connections. Therefore, we are also careful to limit such projects to our immediate area.

What are the most exciting projects you are working on at the moment?

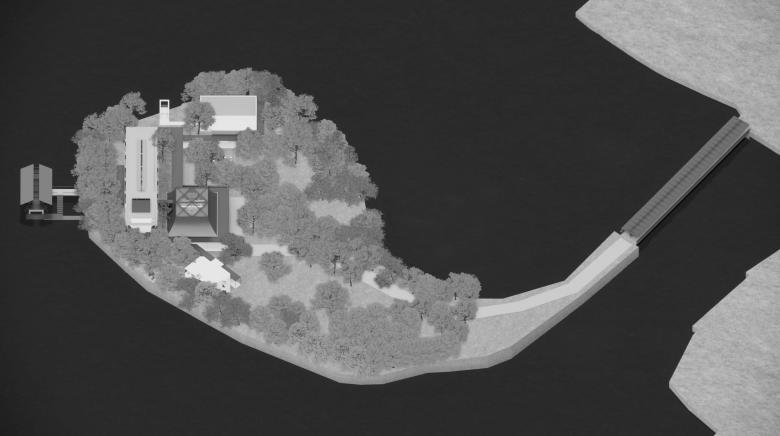

There are three projects that really excite me. One is the renovation of a stone village for fishermen by the sea in Guanyin Mountain in Yongning, Fujian Province. The stone houses are built on the rocks, and the walls and roofs are all made of stones. There are plans to turn them into a site of cultural tourism. The local government has not yet reached an agreement on whether to preserve all the stone houses, but we are trying our best to convince them for a complete preservation.

Another project is a traditional structure in dilapidated condition in the old town of Suzhou. Seen from above, it is part of a beautiful urban fabric, but the partly wooden structure is actually in a ruinous state. It is adjacent to the Chang Garden, a traditional garden from the Qing Dynasty, which makes the project very tempting. As for the architectural style, it is quite a challenge to find a creative way to convert it into a hotel while complying with the city’s particularly strict preservation regulations.

The third one is an abandoned water intake building on an island in Shaoxing’s Jian Lake. It is to be converted into a bookstore. Shaoxing is the birthplace of Jiangnan culture and the hometown of renowned writer Lu Xun [1881–1936]. On the island are several 1980s brick veneer buildings with pediment structures that show a slight influence of postmodern architecture. In the renovation, we try to transform them with themes from Chinese gardens and a literary spatial-narrative approach.