Three Headlines, in Brief

John Hill

15. October 2020

Images via CCNY, Domus, Library of Congress

An architecture school dean resigning, a Pritzker Prize-winning architect writing a letter, and a survey determining if Americans like modern architecture: three headlines discussed briefly.

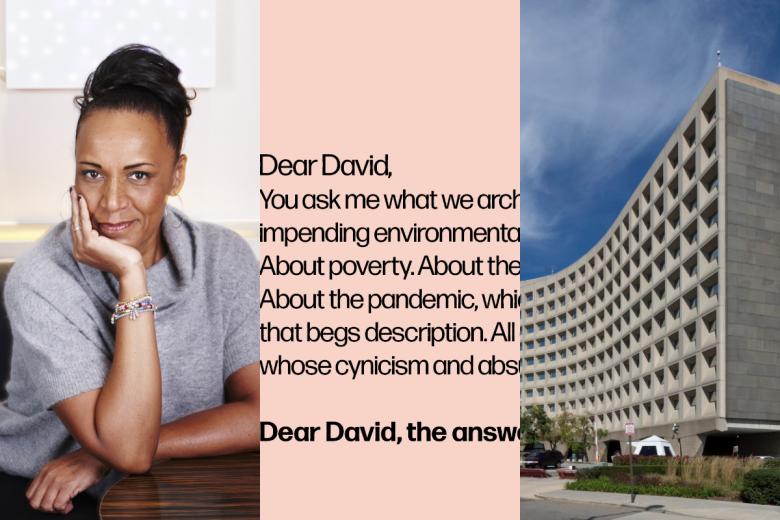

Lesley Lokko Steps Down as CCNY Dean, in 'A Profound Act of Self-Preservation’On October 5, Architectural Record reported that Lokko has resigned as dean of the Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York, just ten months after starting the job. Lokko was hired in 2019 after CCNY (where this writer, it should be noted, attended grad school) was without a permanent dean for a few years. Her appointment was met with excitement and optimism, especially given that Lokko had previously set up a the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg. But as the article reveals, her attempts at instituting change at the school of roughly 400 students were met with a "lack of meaningful support," among other things. Record later published a letter from 16 CCNY students who "believe that Dean Lokko’s vision should have better incorporated the needs and desires of its students."

An article at Inside Higher Ed goes beyond the publicly released resignation letter, which ends with the alarming sentence that Lokko — a Black Ghanaian and Scottish woman — ended her job as "a profound act of self-preservation." Interviewing Lokko, Inside Higher Ed reveals that CCNY's lack of a permanent dean before her created the environment that contributed to her departure, as did a "nonexistent" management culture forcing her to do things a dean wouldn't normally handle, working 18 hours days to achieve her vision, and losing Michael Sorkin, who headed CCNY's urban design program and was instrumental in bringing Lokko to the school.

Lokko's resignation takes effect at the end of January 2021, when CCNY will be in the process of finding a new dean, yet again, and when many eyes will be seeing what Lokko does next.

The Swiss architect responds to Chipperfield's question — what should architects do about "impending environmental catastrophe. About social inequality. About poverty. About the degradation of this planet’s resources. About the pandemic?" — with "the answer is: nothing." The letter doesn't end there, though. It continues with 2,200 more words of advice, some of them contradicting his initial answer: "We can’t change society but we can make a tangible contribution." Then later: "We can’t change society. But at least single projects, like our study of the Swiss landscape, can succeed in being incorporated into real politics." And later still: "So we can do something after all! Architects want to do something; they want to take action."

Although it seems intended to provoke, the letter is worth reading for seeing Herzog's thoughts unfold as he writes, and for illustrating the dramatic differences between Herzog's generation and younger architects today who lean toward architecture having a responsibility to society. Architecture goes through ebbs and flows of focusing on form or addressing social issues; architecture today is squarely in the latter, though Herzog is stuck in the former.

Although the draft executive order tilted "Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again" has yet to reach the desk of President Trump — and hopefully never will — its aim of mandating classical styles for courthouses and other federal buildings is at the heart of a new National Civic Art Society survey conducted by Harris Poll. A little over 2,000 Americans were asked their preference when presented with pairs of photographs of existing federal buildings, one "neoclassical style" and one "modern style." The results? "72% [of respondents] — including majorities across political, racial/ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic lines — prefer traditional architecture for U.S. courthouses and federal office buildings," according to a press release.

The poll seems like an attempt to show that Americans overwhelmingly prefer traditional architecture and therefore the executive order should be signed. (Although the order is dormant, the federal government has included similar language in contract opportunities that basically mandates the same thing.) After all, both the poll and the draft order have in common Justin Shubow, the president of the National Civic Art Society, a nonprofit "advancing the classical tradition in architecture, urbanism, and their allied arts," and a Commissioner on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, as appointed by Trump. He is tenacious, even though his most public fight — in stopping Frank Gehry's Eisenhower Memorial — was unsuccessful, after nearly ten years trying.

Yet the survey is unsettling, mainly for its tactics. Should architectural issues be decided through strictly exterior photographs of buildings in oppositional styles? Is there no nuance, or are choices in architecture simply "this or that"? Is architecture limited to the facades of buildings, how they are seen from the outside? And most importantly, should a preference for one style over another lead to an imposition of the preferred and the demise of anything else?