10 Highlights from 'Even Better Than the Real Thing'

The Architectural Aspects of the 2024 Whitney Biennial

John Hill

14. March 2024

Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House by Kyan Williams (All photographs are by John Hill/World-Architects)

Occupying two full floors and multiple terraces of the Whitney Museum of American Art's Renzo Piano-designed building in New York's Meatpacking District, the 81st edition of the Whitney Biennial, subtitled Even Better Than the Real Thing, aims to provide a space where difficult ideas — about race, gender, technology, politics, nature, and other issues — can be engaged and considered. World-Architects previewed the exhibition and presents some highlights.

According to Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli, curators at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing is “an exhibition that unfolds as a set of relations, exploring the challenges of coming together in a fractured moment.” The exhibition they co-organized, opening on March 20 and running until August 11, focuses on “ideas of ‘the real’ to acknowledge that, today, society is at an inflection point, in part brought on by artificial intelligence challenging what we consider to be real, as well as critical discussions about identity.”

While such serious issues are immediately clear in some of the contributions by the roughly four-dozen artists and collectives on display across the museum, one of the most pleasing aspects of the Biennial is its physical openness: the breathing room that comes from fewer artists compared to previous iterations. Many of the artworks, in turn, are room-sized but fairly empty, using colors and moving images to provoke and tell stories. They are sculptural, but with enough room around them to be appreciated by many people and from different vantage points. And they are grand, almost architectural in scale, material, and texture.

Put another way, in addition to its messaging, the art on display can be appreciated for its architectural aspects — something we did with this roundup of ten highlights from Even Better Than the Real Thing.

Architectural Immersion

Most visitors will start at the top by taking the elevator to the sixth floor, where they will encounter Afferent Nerves by P.Staff, a sparse room bathed in yellow light and capped by a live electrical net that is — thankfully — out of reach.

Elsewhere on the sixth floor is Diane Severin Nguyen's In Her Time (Iris's Version), a film about the making of a film about the Nanjing Massacre of 1937, whose brutality is accentuated by the blood-red surroundings.

Stepping off the elevator on the fifth floor, visitors immediately see a wall covered in the image of a large flower pierced by a round portal that leads to an equally large room for watching Tourmaline's Pollinator, a film that celebrates Black trans activist and performance artist Marsha P. Johnson (1945–1992).

The most impressive immersive installation in the Biennial is Isaac Julien's Once Again …. (Statues Never Die), a film in which actors portraying Alain Locke (1885–1954) and Albert C. Barnes (1872–1951) converse about the legacies of Black artists across modern history. The film is projected on five screens in a dark space with reflective walls.

Architectural Light

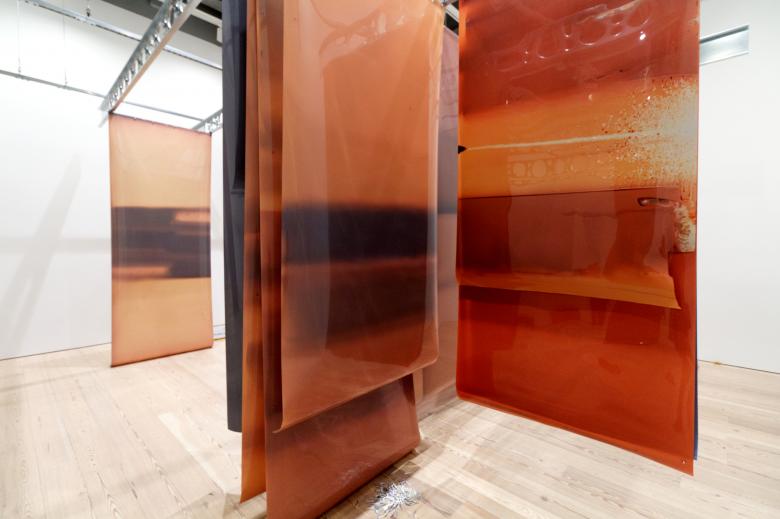

Lotus L. Kang's In Cascades is the sole occupant of a gallery whose two entries invite visitors to wend their way through large sheets of film suspended from steel joists.

The sheets of film were exposed to varying conditions of light in multiple locations, a process the artist refers to as “‘tanning,’ likening the film surface to skin and bringing the material back to ideas of the body, particularly its permeable relationship with environments.”

The positioning of Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio's Paloma Blanca Deja Volar / White Dove Let Us Fly next to the glass wall of the sixth-floor terrace made it hard to photograph during our morning visit …

… but the location is intentional, as the sunlight will warm up the tree amber that encases archival documents and other found objects, changing the shape of the sculpture over the five-month run of the exhibition.

Architectural Form

The fragility of political institutions — long seen as stable in the USA, at least from the end of the Civil War until January 6, 2021 — is expressed in Kyan Williams's Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House through a “sinking” sculpture depicting the north facade of the White House (see photo at top).

The choice of earth for the sculpture is apt, rooting the piece in labor (“working the earth”) but also giving the piece a prominent texture that should, like Aparicio's nearby sculpture in amber, subtly transform its surface over the course of the Biennial.

Dala Nasser's Adonis River is a large-scale sculpture that defines a space in a fifth-floor gallery through two L-shaped constructions: one a row of columns and one of perpendicular walls, each covered in bedsheets that feature rubbings of rocks by the Adonis Cave and Temple in Lebanon; sheets further dyed with iron-rich clay.

Although framed simply in lumber, the sculpture articulates bases and capitals in a way that alludes to ancient temples in stone and hints at how such stone buildings evolved from wood buildings.

Architectural Scale

If any piece in the Biennial manges to make visitors uncomfortable through the most minimal, abstract of means, it is Charisse Pearlina Weston's un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), made of six panes of dark glass suspended at an angle over museum-goers' heads.

When seen at just the right angle, Weston's jarring plane of glass effectively disappears.

Located on the expansive fifth-floor terrace overlooking the High Line and Hudson River, Torkwase Dyson's Liquid Shadows, Solid Dreams (A Monastic Playground) is suitably monumental, made up of three extruded shapes that visitors can touch, sit on, and step across.

“Together, the monumental arcs, implied gestures, and surrounding natural light,” per the Whitney, “articulate changing abstract shapes over the course of each day and night.”

Related articles

-

This Week in Lawsuits

2 weeks ago

-

Ryoji Ikeda's ‘data.tecture [nº1]’

2 weeks ago

-

Richard Serra, 1938–2024

1 month ago

-

Inside ‘Tropical Modernism’

1 month ago

-

Dreams of Cities in Wood

1 month ago