Interview with Xu Tiantian

Activating Neglected Local Resources with Minimal Intervention

Eduard Kögel

12. octobre 2022

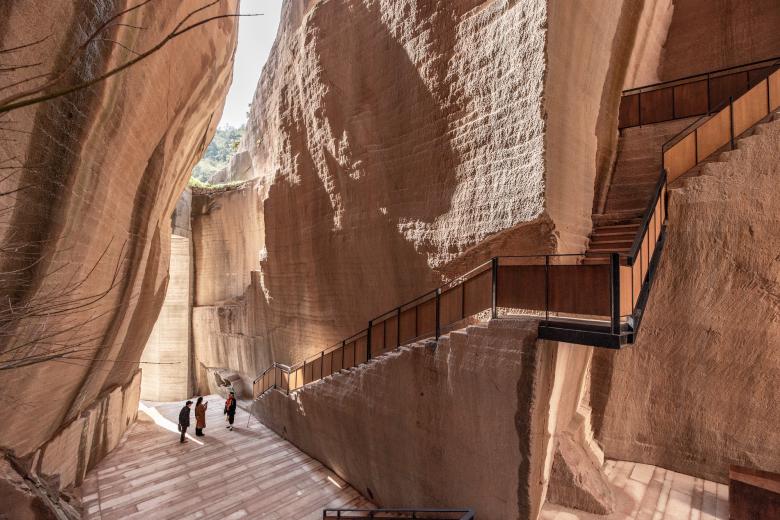

Quarry #9 in Jinyun County (Photo © Wang Ziling)

At the beginning of October, Xu Tiantian and Tei Carpenter were in Berlin at ANCB, The Aedes Metropolitan Laboratory, for a workshop with their students from Yale University School of Architecture. On this occasion, Eduard Kögel spoke with Xu Tiantian of DnA Design and Architecture about her teaching concepts and design strategies for rural contexts.

Eduard Kögel: You are currently teaching at Yale University. What is your program for educating today’s students?Xu Tiantian: I am currently a visiting professor at Yale University, teaching an advanced design course with New York architect Tei Carpenter called Reinventing Referinghausen. If I could, I would love to take my students to China, to share with them all that we have done in terms of methodology and social engagement and how that has translated into each architectural action. Because of the travel restrictions in China due to Covid-19, we had to look for an alternative site for this studio. I am a practicing architect from China, the students are from an American university, and we are now working with the German village of Referinghausen in Sauerland, where the German architect Christoph Hesse has been working for years. With this project we can see how our working method can work in a different context.

Reinventing Rural Regions at ANCB in Berlin, Christoph Hesse, Xu Tiantian, Tei Carpenter (Photo © Liz Eve)

What does that mean in practice? You went to this place and talked to different people there?When we started the semester, I knew nothing about the village and this area; it was a new journey for me as well. I had the same starting point as my students and I wanted to learn together with them. We spent a month at school first researching and analyzing, working on social strategy in close contact and exchange with the local architect Christoph Hesse and the village representatives. In our travel week, we just had the opportunity to test our assumptions for the first time with ideas from the village, the community, and local needs. It was as new for us as it was for the students. It's amazing how our students could work so closely with the villagers and the community, who are really generous and very open to new ideas. We had very intense discussion and workshops with the village community and local authorities.

On the way to the village, we visited documenta fifteen in Kassel, curated by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa. Their concept is based on collective exchange and community engagement. The idea is to create socially engaged meeting spaces in the city, like underground tunnels or street corners, which they programmed with events, conferences and even parties. We found the concept of “Lumbung” and the focus on collective sharing to have similar values with our architectural approach in rural villages.

Students in Referinghausen (Photo © Xu Tiantian)

You have a lot of experience with discourse with local populations and authorities, for example in the Songyang projects. Do you see major differences when you compare the Chinese and German situations?No, there is not much difference. Maybe when you talk about the two countries and their political system. But in these communities, everything is connected at the local level, and the local government is very close to the residents, both in Songyang and in Referinghausen. They all grew up in the region and are willing to bring to their hometown a better life and a better future. On this scale, you can really work together in a kind of networked partnership; the system is already in place. The mayor in Referinghausen is really championing new things and getting them off the ground. You need that kind of leadership at the local municipal level. And that’s how we worked in Songyang County as well. The mayor of the county, the head of the culture department, and also the local village leaders are pushing things forward. We propose and contribute ideas, but we also learn from them as they look for solutions to make the ideas work. That’s different from being commissioned for a project.

It is their hometown. They have a great sense of responsibility and also authorship for planning the future. And that is the same everywhere, in Referinghausen and in Songyang. Of course, some communities are more open to new ideas, others are more likely to hold on to what they already have, or even be stubborn. You have to deal with this difference in openness and figure out at what level you can intervene with design and architecture. Ultimately, it’s about people; it’s not about making a design without talking to people. At a rural level, it’s about trust, it’s about property, it’s about regulations, it’s about people’s personal wants and needs. At that level, it’s not the same as master planning in an office; it’s defined by communication, by discussion.

Workshop in Referinghausen (Photo © Xu Tiantian)

Is it a process of opening minds and clarifying how to inspire residents?You also have to take reality into account and work with it. That makes the final design even more flexible and adaptable. It's not about superimposing, but behind these strategies is the community, the people, a collective that makes up the culture.

That’s why we say it’s co-authorship. It’s a collective design process that involves people. It’s not about making drawings; it’s about finding the best solution and discussing it. You have to take people as the context, not just the topography, existing buildings, or forms. That’s what’s lacking in our education. You have to engage, especially in the rural context, but also in the urban neighborhoods. In the city, it’s also about community.

Each neighborhood is different and has its own identity or culture. It is a collective consciousness of what they want for their area, but it is also a different community culture, urban and rural.

A village in the valley of Songyang County (Photo © Wang Ziling)

As an architect, you may get to a point where you have to abandon your own design ideas because people on the ground are contributing ideas and going back to known solutions. How do you deal with that?Looking back, I have to say that I was naïve at the beginning: we didn’t understand local architecture and its solutions at some level. When you really enforce something that you learned in school or in the cities, it often doesn’t fit; it’s very difficult and it creates a lot of frustration. It’s also great to learn from local people, because there is an amazing building culture in every region. On the other hand, it’s also strategic to take advantage of local know-how and building culture. Sometimes you have to train craftsmen in certain techniques because they are almost lost. It is also advantageous to take the material from the region.

The beauty of vernacular architecture cannot be denied or ignored when working in rural areas. This is evident in several aspects. It is a strategy to involve the community, and on the other hand, it facilitates the process when working with co-authorship. As architects, we have to take the lead, but in many of the projects we’ve done, the details are not typically articulated from an architect’s point of view. Yet they reflect the local building style. I think that’s acceptable and even very beautiful because it grows in its own place and comes from local people. The locals not only build, but sometimes they also design. They have a knowledge that has been passed down through generations.

Tofu Factory in Songyang (Photo © Wang Ziling)

Has your approach to interacting with local communities changed over the years since you started working in the countryside?When I first came to Songyang, I had no experience in rural areas. It was an underdeveloped region, and the communities had a different approach to modern life and certain expectations of architecture. But as an architect, how can you make a social and economic impact and also have a cultural influence at the local level? Because of my training and practice in an urban context, I had no experience with such complex social contexts. We had no training for this engagement.

This is exactly what we are trying to bring to our studio, to architectural education. Student engagement should not be separate from social development. Rather, it should become a systematic methodology to broaden the context. I also see teaching as a practice to bring students into reality and to understand who they are building for. This is a really important point in our whole practice, though it is often missing in the architecture profession. Architecture can respond to a regional problem and spark further discussion. That’s my view of teaching. But as a professor, you learn together with the students, and you are sort of the curator of the team that works together. The students learn how to collaborate with the villagers and how that translates into architecture in their individual designs. In this advanced studio, we first worked in groups and later each student will work on their own project. By working in such a village community, it is also possible that some of the projects can actually be realized.

Rice Wine Factory in Songyang (Photo © Wang Ziling)

You have a lot of experience compared to the students. How do you use this to facilitate the process of engagement and communication between the local community and the students?This is a very similar process to the one we were already involved in at Songyang. There are many uncertainties in this process, and that’s how it works in reality. These uncertainties are something very exciting, because they can lead to something that is not predetermined. New possibilities open up. The semester has only been going on for a month, but we’ve already come across so many new possibilities. Discussing with local architect Christoph Hesse, the mayor of Referinghausen, and community members, new perspectives are emerging for the students. I am really proud of our students; they have had really exciting and successful community meetings where they have received very positive and helpful feedback.

Especially after over two years of pandemic.

Face-to-face communication is so important in our professional training.

Huming Tea Space in Jingning County (Photo © Wang Ziling)

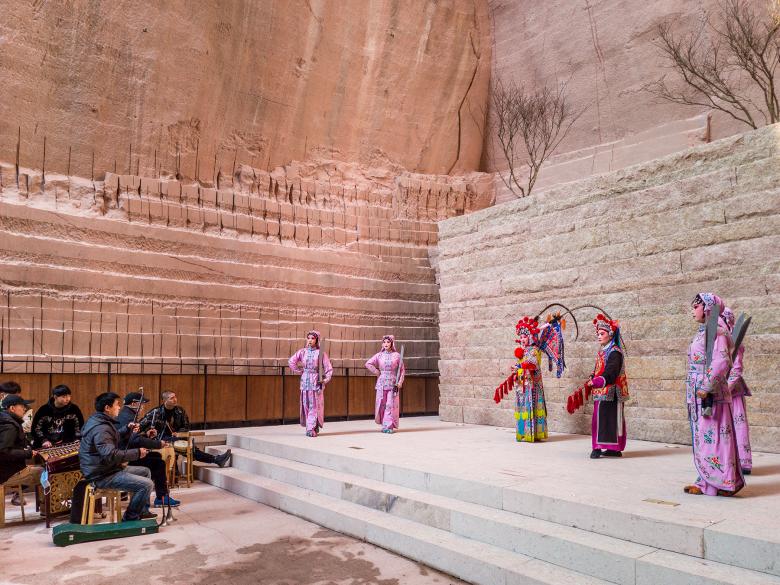

With your studio, you are involved in various projects in different regions of China. You carry with you the experience from Songyang and other places. How do you apply it to these new places?You always start from the outside with a fresh look at local resources. This is the most important aspect for the engagement of architects in rural regions. It leads to a kind of reassessment of the resources available on the ground in order to reform the local identity. We worked successfully in the agricultural context of Songyang County, and then neighboring Jinyun County, with a large number of quarries, became our client. But it’s very different there because it’s so technical; the history of the quarries goes back 1,000 years. Safety was the first priority in the work to transform these quarries. Some quarries have already collapsed, and many more are in critical condition. The first priority was to solve the safety problem, but it is also an ecological problem on a regional scale.

With minimal design intervention, these spaces could be transformed into something significant, with a new public program for villagers who have a strong emotional connection to these places. It’s not about the signature of the architects, but about design being a supporting element to make these spectacular, monumental spaces accessible. It wasn’t just their craftsmanship that was required; because they are so emotionally connected to the quarries that they took over these places as soon as they were completed. So, it’s about how to activate neglected local resources with minimal intervention.

Quarry #9 in Jinyun County (Photo © Wang Ziling)

Are you currently working with your studio on new projects that require a special approach?We are working on a new project with tulou buildings, the rammed earth buildings of the Hakka and Minnan peoples in Fujian province. These are defensive buildings with communal living. Forty-six tulou are on the UNESCO World Heritage list, but what is happening to the other thousands of tulou in the wider region? Many of them are already in ruinous conditions. A few still have some original inhabitants, but most of these massive buildings are empty and abandoned. For many locals they are considered invaluable. We first submitted this project to the local government to demonstrate with seven tulou buildings how they can be repurposed into public facilities or mixed-use spaces. With the help of architecture, these under-appreciated buildings can take on a new role in the formation of a local identity.

Tulou courtyard (Photo © Xu Tiantian)

Back to your teaching. Your pedagogical approach sounds like you train agents to recognize existing local cultural, craft and building resources that could become hubs for community renewal.We’re trying to connect local knowledge with modern needs and solutions to make rural areas more resilient. It’s about preserving local culture and strengthening local identity in a contemporary way, and providing local people with compelling solutions for the future. There is no blueprint for this, only the diverse experience of reality. The know-how and knowledge of how to do this must also be taught at our universities.