Nickels from Heaven

John Hill

6. October 2020

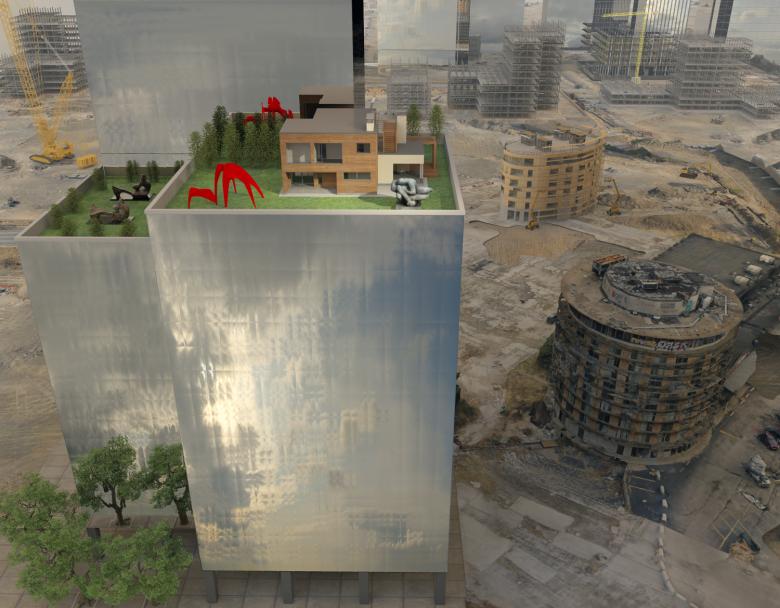

Tim Portlock, Sculpture Garden, 2020. Archival pigment print, 94 1/2 x 123 inches. Courtesy the artist.

One of three contributions to this year's Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM) is Tim Portlock's Nickels from Heaven, a series of large-scale prints that dramatically depicts cityscapes in the midst of major transformations.

This year's Great Rivers Biennial is the ninth collaboration between CAM and the Gateway Foundation, which established the program together in 2003 with the aim of supporting artists in the greater St. Louis area. Nearly ninety applications were submitted for the most recent Biennial, with the jurors selecting ten finalists in June 2019 and subsequently making studio visits to select the three winners. Kahlil Robert Irving, Tim Portlock, and Rachel Youn each received an unrestricted $20,000 honorarium and now have their work on display at CAM.

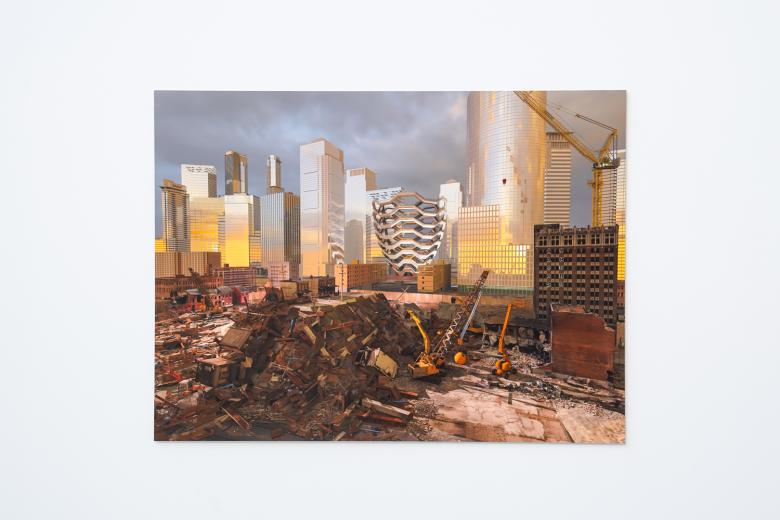

Tim Portlock: Nickels from Heaven, Great Rivers Biennial 2020, installation view, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, September 11, 2020–February 21, 2021. Photo: Dusty Kessler.

Portlock's images should be appealing to architects, not only for the urban/architectural subject matter — Thomas Heatherwick's highly recognizable Vessel makes an appearance in one print, for instance — but for his process, which incorporates computer modeling and animation and in all likelihood uses some of the same software as architects. (CAM members can actually get a behind-the-scenes virtual peek at his process on October 28.) In addition to creating art from modeling, rendering, and animation software, the Philadelphia- and St. Louis-based artist is an associate professor in the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Art at Washington University in St. Louis.

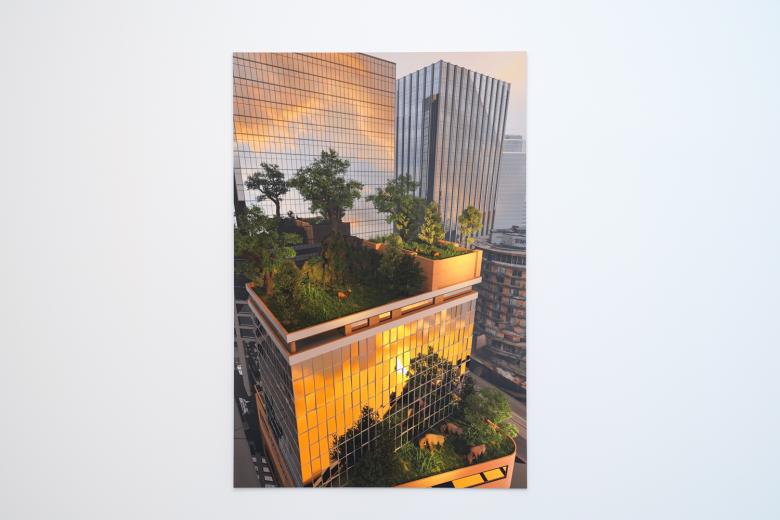

Tim Portlock: Nickels from Heaven, Great Rivers Biennial 2020, installation view, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, September 11, 2020–February 21, 2021. Photo: Dusty Kessler.

Nickels from Heaven takes its name from the 1936 Bing Crosby film Pennies from Heaven, which Portlock describe as "81 minutes of escapism" from the Depression gripping the United States at the time. Apparently adjusted for inflation, Portlock's Nickels series is set among the numerous crises that have been unfolding since the 2008 economic collapse, when booming real estate has transformed cities while also masking economic and social inequalities and other concerns. Although the prints were made before the pandemic, the cityscapes free of people are appropriate to our moment, as if they capture a time when construction halted and people quarantined themselves indoors.

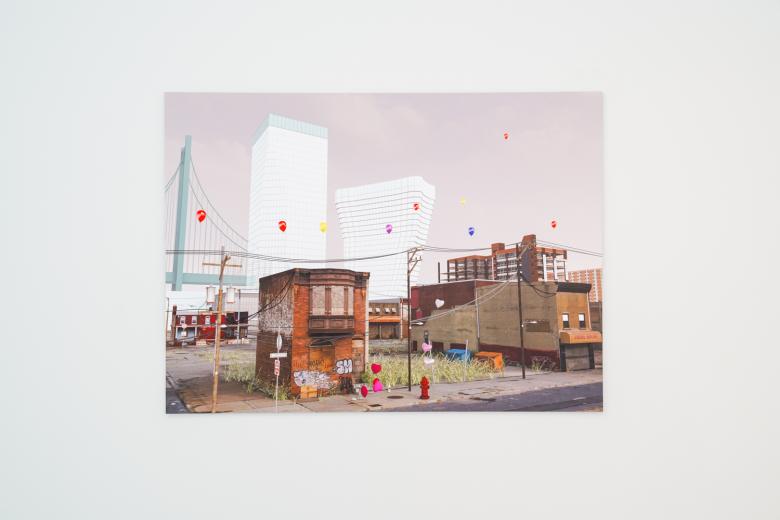

Tim Portlock: Nickels from Heaven, Great Rivers Biennial 2020, installation view, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, September 11, 2020–February 21, 2021. Photo: Dusty Kessler.

Another interesting aspect of Nickels from Heaven is the way the urban environments look real but are actually fictionalized, made up of often real structures from various cities transplanted into digitized environments. So at first glance the image with Vessel at its center looks unmistakably like Hudson Yards, but a closer look reveals that the surrounding buildings do not match what is there, plus the rail yard upon which the development is built is nowhere to be found. Put another way, while the prints look like photorealistic representations of reality in the tradition of Richard Estes, the fictional settings amplifies their social commentary, which CAM sums up well as "the divergence between the idealism of American exceptionalism and the lived realities of contemporary American cities with declining populations."

Tim Portlock: Nickels from Heaven, Great Rivers Biennial 2020, installation view, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, September 11, 2020–February 21, 2021. Photo: Dusty Kessler.

Nickels from Heaven is on display as part of the Great Rivers Biennial: Kahlil Robert Irving, Tim Portlock, and Rachel Youn at CAM from September 11, 2020 to February 21, 2021.